The Editing Company

Toronto, Ontario

RECENT POSTS

TEC Blog

Categories

Show All- Editing

- Grammar

- Usage

- Style

- Editor/writer

- Publishing

- Business

- Writing

- Writers support group

- Event

- Proofreading

- Copyright and permissions

- Usage

- Book reviews

- Editing new media

- Technology

- Books & libraries

- Ttc stories

- Editing & marketing

- Office happenings

- Social media & community

- Language & editing

- Social media

- Editing & marketing

- Indexing

- Book design

- Tec clients

- Guest blogger

- Creative women doing sixty

- Book clubs

- Books and reading

- Ebook technology & services

- Editing numbers

- Editing & technologies

- Opera, movies

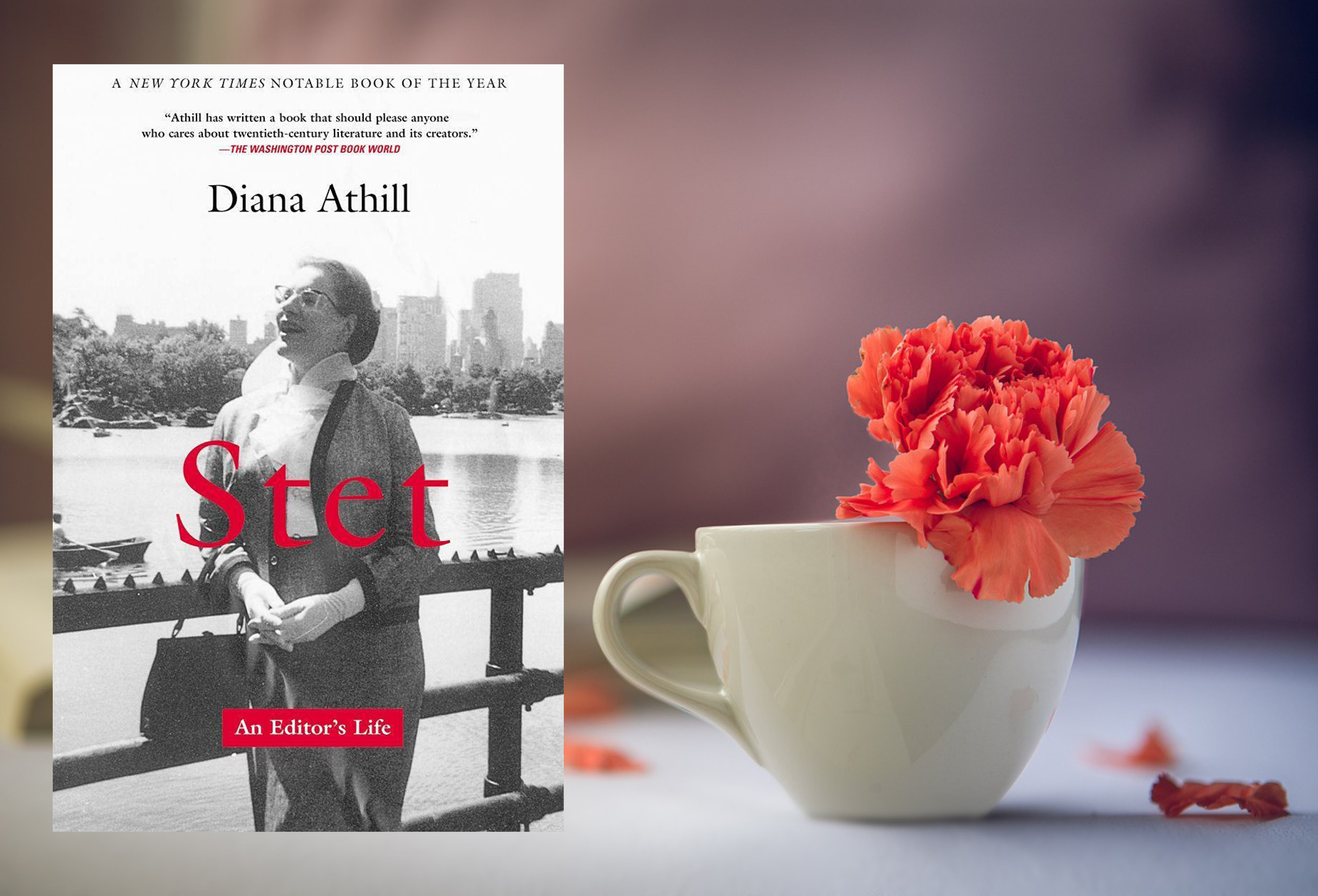

A Review of Diana Athill’s Stet: An Editor’s Life

by Samantha Rohrig

Published at 2023-10-24

In a departure from the other books reviewed in this series, a wonderful collection of editorial “how-to” manuals and grammar guides, Diana Athill’s Stet (Granta Books, 2000) provides a candid insider’s look at the life of an editor and the wider world of independent publishing—“run by badly-paid women and a few much better-paid men” (p. 56)—in post-war England.

When I first happened upon this title while browsing the shelves of a thrift store earlier this year, I immediately scooped it up; I had never heard of Diana Athill, but I felt a strong sense that as a bourgeoning young (to the field, at least!) editor, this was one of those books I had to read. When several months later I was asked if I would like to review the book, which had remained untouched on my desk since my first bringing it home, I suddenly became quite apprehensive. What did I know about the London publishing scene in the second half of the twentieth century? What did I even know about working at a publishing house for that matter? And not only had I never encountered the name Diana Athill before, but of the “great literary figures” mentioned on the book’s back cover I only vaguely recognized one (Philip Roth) and was completely in the dark about the other four (Jean Rhys, Norman Mailer, V. S. Naipaul, and Mordecai Richler). No, I thought, shaking my head and slowly backing away, this book wasn’t for me after all.

Happily, I was very wrong.

“Let it stand”

The title of the book, a proofreader’s instruction meaning “let it stand,” cleverly encapsulates Athill’s purpose for writing: to rescue from deletion the memorable moments of her life as an editor that time and age were already beginning to threaten (Athill, who sadly died in January 2019, was in her eighties at the time of writing). The book is evenly divided into two parts. The first half covers in chronological fashion Athill’s career in publishing, most of which she spent working closely with her one-time-lover-turned-friend, André Deutsch, first at his publishing firm Allan Wingate in the late 1940s (started with a mere £3,000 in capital), and then for the next forty or so years at André Deutsch Limited, where Athill was a founding director. In the second half—illustrating the truth of “that ancient cliché about working in publishing: You Meet Such Interesting People” (p. 7)—Athill reminisces, through a series of vignettes, about her relationships (the professional often blurring into the personal) with the six authors who, for various reasons, had the most memorable impact on her career and life.

Through it all Athill writes with the clarity and polish you would expect of someone who spent her professional life ensuring others did just that, but it is her voice—insightful, funny, frank, at times cutting but always, in the end, empathetic—as well as her willingness to admit to and examine her own deficiencies as a person and a publisher that quickly draw you in and keep you invested, even when you are largely unfamiliar with the period and personalities she is describing, as I was.

“You will have to earn your living”

One of the things that most struck me about the book was how so many of Athill’s observations and sentiments not only still rang true but even felt intimately familiar to me, despite the distance of time and circumstance that separate us (Athill was born in 1917 into a decidedly upper-middle-class family; she attended Oxford, where her great-grandfather had been Master of University College; and she got her first job at the BBC through a personal contact in its requirement office during the Second World War). She captures exactly the feeling of incredulity I experienced when I first realized, rather later than one might wish, that reading—not a mere pastime but an essential part of my life since childhood—could be a duty (p. 10), and I certainly share with her the opinion that “the greatest advantage [editing] offers as a job is variety” (p. 65).

“You don’t necessarily become a best-seller by writing well”

Though not an editorial guidebook strictly speaking, Stet naturally offers much insight into the business of publishing (the buying and selling of “the products of people’s imaginations”; p. 6); descriptions of the many hats an editor must wear (including that of “nanny” and “therapist”); an overview of the more dutiful aspects of editing (e.g., “the need to work conscientiously in spite of being bored, and to put oneself at the service of books that are not always within one’s range”; pp. 69–70); several editorial ground rules to live by (including the absolute and universal rule that no change of any kind can be made without the author’s approval); the nature of the author–editor relationship (“friendship, properly speaking, between a publisher and a writer is … well, not impossible, but rare”; p. 132); and nuggets of sage advice (“An editor must never expect thanks … We must always remember that we are only midwives—if we want praise for progeny we must give birth to our own”; p. 38).

Enlightening too is Athill’s shrewd understanding of the book market, which even two decades after the publication of Stet, and over half a century since the height of Athill’s editing career, still convinces:

People who buy books … are of two kinds. There are those who buy because they love books and what they can get from them, and those to whom books are one form of entertainment among several. The first group, which is by far the smaller, will go on reading, if not for ever, then for as long as one can foresee. The second group has to be courted. It is the second which makes the best-seller, impelled thereto by the buzz that a particular book is really something special; and it also makes publishers’ headaches, because it has become more and more resistant to courting. (p. 117)

“It was my job to listen to his unhappiness”

Besides the fascinating portrait of post-war publishing that Stet paints throughout, it is also just a good read. This is especially true in its second half, which offers candid character sketches of six of the most memorable (rather than the most famous) authors with whom Athill worked: Mordecai Richler, Brian Moore, Jean Rhys, Alfred Chester, V. S. Naipaul, and Molly Keane. I could have easily become bored here, as I had never heard of these authors let alone read any of their more notable works. Instead I found myself amazed at what I now know to be the brilliance of Rhys’s prose given her ineptitude in most other matters of life. I was moved by the tragedy of Chester’s final years and the loss of such a talent to mental illness. I was shocked by the unguarded way Athill describes Naipaul (the most celebrated of the bunch), who comes across as both pompous and not a little cruel. This is a testament to the skill with which Athill weaves her narratives together.

These vignettes also provide opportunities for Athill to reflect with both wisdom and clarity on a range of issues as relevant now as they were then, from gender inequality and sexism to mental illness, ageing, racism, and the deleterious legacy of British imperialism. The effect is such that even though Athill provides few concrete details about her own life outside of her work, by the end you still feel as though you have somehow gotten to know her.

Final Thoughts

Contrary to my initial trepidation—and despite a few references that went straight over my head (I had to Google “P. G. Wodehouse” to make sense of Athill likening a colleague to Bertie Wooster)—Stet: An Editor’s Life was, as it turns out, very much for me. It kept me engaged from start to finish and, perhaps best of all, has furnished me with an impressive list of new names and titles to add to my ever-growing “to read” list. I would first and foremost recommend this book to all in the publishing field, from publishing interns to managing directors and everyone in between. Readers interested in English-language literature of the mid-twentieth century and those who simply enjoy amusing and compelling memoirs will also not be disappointed.

In one memorable passage, Diana Athill sums up why books have meant so much to her over the course of her life: “It is not because of my pleasure in the art of writing, though that has been very great. It is because they have taken me so far beyond the narrow limits of my own experience” (p. 115). I hope she would be pleased to know that her book has done exactly this for me.

Samantha Rohrig is TEC’s academic and non-fiction editor and proofreader. In her freelance practice she specializes in editing and indexing for academic publications in the fields of classics and history. She can be reached at samrohrig@live.ca.